Trump's Regulatory Reform and the Manufacturing Sector

Advancing American manufacturing was a central part of the Trump campaign’s economic platform. So far, so good.

According to a survey undertaken by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM), manufacturing growth in December 2017 accelerated and was broad based, with 16 of 18 manufacturing industries reflecting economic growth. The ISM also reported that December was the 16th consecutive month of growth for manufacturing (and the 103rd in a row for the economy as a whole). Finally, in November 2017, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that U.S. manufacturing GDP increased by 11.5 percent of U.S. GDP in the second quarter of 2017 — an all-time high.

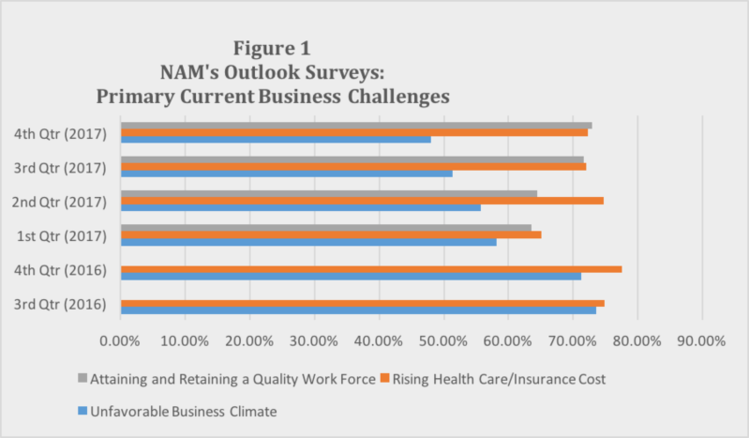

How much of this manufacturing expansion can be attributed to the Trump administration’s regulatory reform? A partial answer can be gleaned from studies undertaken by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). A January 2017 NAM study, “Holding Us Back: Regulation of the U.S. Manufacturing Sector,” found that manufacturers faced 297,696 restrictions on their operations from federal regulations. Ninety-four percent surveyed reported that the regulatory burden increased over the past five years, with 72 percent saying “significantly higher.” In the Manufacturers’ Outlook Survey, taken just before the election, about 74 percent of NAM members cited an “unfavorable business climate, e.g., taxes, regulation” as a “primary current business challenge.” (See Figure 1 below.)

Fast-forward a year. The fourth quarter 2017 NAM survey shows “unfavorable business climate” plummeting to 48 percent — a decline of 25.6 percent since Trump’s election — and ranking well behind other challenges. According to NAM, the decline reflects “manufacturers’ belief that the administration will continue to provide regulatory relief and lawmakers will push tax reform forward.”

What has the Trump administration done to earn this optimism?

First, immediately after entering office, Trump placed an executive hold on approval of administrative rules (with exceptions for emergencies). Agencies withdrew or delayed 1,579 planned regulatory actions, reflecting all such changes from Fall 2016 to Fall 2017.

Second, the President issued an executive order requiring executive departments and agencies to issue two deregulatory actions for each new regulation, with the cost of the latter to be completely offset by the former. In FY2018, federal agencies plan to finalize three deregulatory actions for every new regulatory action.

Third, in January 2017, Trump signed a directive to expedite reviews of — and approvals for — proposals to construct or expand manufacturing facilities and to reduce regulatory burdens affecting domestic manufacturing. An October report from the Department of Commerce, taking into account comments from stakeholders like corporations and industry associations, made three major recommendations:

1. Each federal agency’s Regulatory Reform Task Force should deliver to the president an “Action Plan” in response to all permitting and regulatory issues highlighted in the manufacturers’ responses in the Federal Register.

2. An annual, open forum should be established for federal regulators and industry stakeholders to evaluate progress in reducing regulatory burdens.

3. The administration should use existing authority to extend streamlined permitting procedures established in the FAST Act (Fixing America’s Surface Transportation) to any project that will result in a significant, immediate economic benefit to the U.S.

The report also recommends that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) review of agency rules be reaffirmed in the following ways:

1. Cost-benefit analysis methods should be refined and more rigorously enforced.

2. Cumulative costs should be weighed where appropriate.

3. Regulations should not impede innovation.

4. There should be meaningful public engagement prior to proposing significant rules.

5. Regulations should be more sensitive to the impact on small business.

6. Regulations should only be enacted and enforced when there are adequate resources available for review, implementation, and oversight.

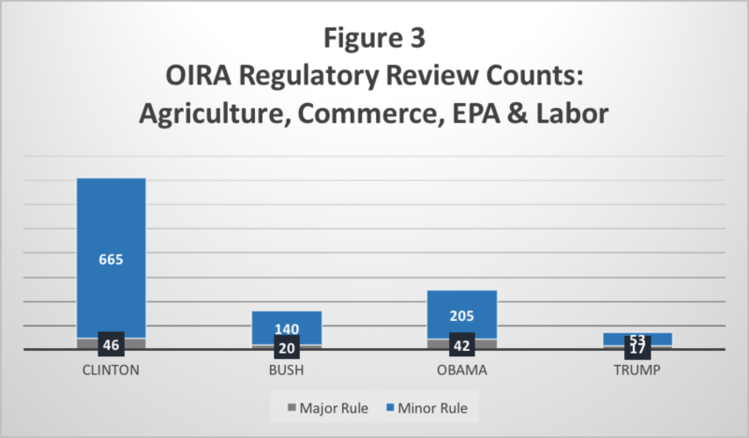

The OIRA’s 2017 regulatory reviews (Figure 2 above) show that this “gatekeeper” office has approved significantly fewer major rules — those having an economic impact of at least $100 million or meeting other criteria — and dramatically fewer “minor” rules than each of the previous three administrations. Compared to the first year of the Obama administration, the Trump administration has approved 51.3 percent fewer major rules and 70.2 percent fewer minor ones.

The data are similar if we look at departments and agencies that impact manufacturing: Agriculture, Commerce, the EPA, and Labor. In these areas, the Trump administration has approved an impressive 59.5 percent fewer major rules and 74.1 percent fewer minor rules than the Obama administration.

There’s more to be done. Congress has four bills on its agenda dealing with overregulation. The Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017 (H.R. 5) combines six previously passed bills to eliminate “overly burdensome red tape and regulation.” The Searching for and Cutting Regulations that are Unnecessary Burdensome (SCRUB) Act (H.R. 998) establishes a commission to identify individual rules that should be repealed to lower costs. The Regulatory Integrity Act (H.R. 1004) would restrict the use of agency funds to advocate on behalf of administrative rules. And, finally, the OIRA Insight, Reform, and Accountability Act (H.R. 1009) would codify executive branch regulatory review procedures.

While all these bills were successfully passed in the House, they have been languishing in the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs since early last year. However, passage of these bills would give the Trump administration more tools to improve the manufacturing sector’s operating environment — and thus help fulfill the president’s promise to grow the economy by stimulating American manufacturing.

Thomas A. Hemphill is professor of strategy, innovation, and public policy in the School of Management, University of Michigan-Flint and a policy analyst for the Heartland Institute in Chicago, IL.