When America’s founders created three branches of government, they intended for the judiciary to place a check on the other two branches and remain above the fray of partisan politics.

Over 200 years later, America’s judicial branch has instead become perhaps the single biggest flash point in our political system, with every new Supreme Court nomination greeted by increasingly apocalyptic rhetoric and viewed by partisans on each side as a titanic, zero-sum battle over everything they believe in.

Even as the Senate barrels ahead toward a vote on President Trump’s Supreme Court Justice nominee Amy Coney Barrett, Americans need to start thinking hard about how we can turn down the temperature on future nominations and create a less random, more orderly, and more bipartisan process for getting justices on the Court.

The process we have now doesn’t work — and it hasn’t worked for a long time.

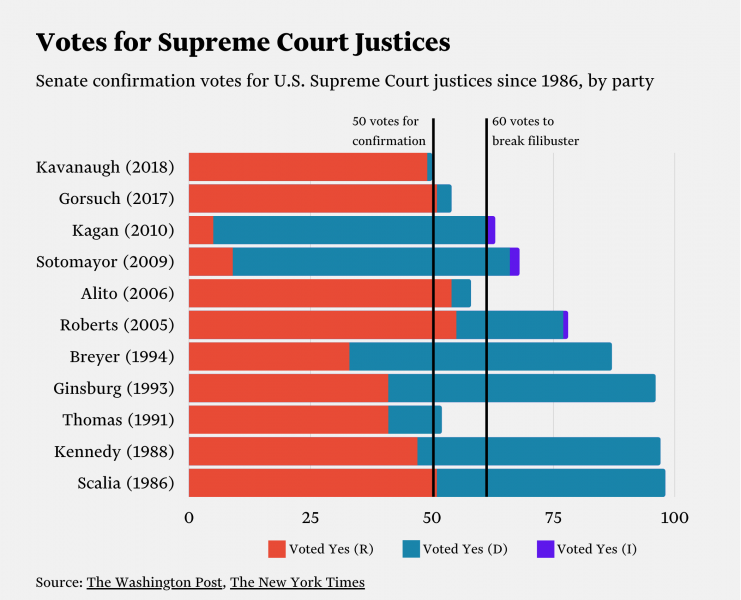

Supreme Court Confirmation Vote Margins Keep Getting Smaller

In 1993, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was confirmed to the Supreme Court by the Senate in a 96-3 vote. The 41 Republican senators who voted to confirm Ginsburg almost certainly didn’t agree with her judicial philosophy. But they believed — as senators throughout most of U.S. history did — that a president had broad discretion to put forth nominees who shared their judicial views and that the Senate’s “advice and consent” role meant senators were supposed to ensure the president’s nominee was competent, qualified, and free of corruption or conflicts of interest.

But now, Supreme Court confirmation votes — like most everything else in Congress — have become almost entirely partisan exercises as demonstrated by the increasingly partisan vote breakdowns of the last 11 Senate confirmation votes.

Procedural Hardball

In 2014, then Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid—frustrated by Republicans’ refusal to consider three of President Barack Obama’s nominees to the federal US Court of Appeals—eliminated the filibuster for federal judicial nominations, excluding those for the Supreme Court.Then Minority Leader Mitch McConnell reacted with a warning to Democrats: “You’ll regret this, and you may regret it a lot sooner than you think.” Sure enough, in 2016, now Majority Leader McConnell refused to even allow a vote on President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland. And in 2017, McConnell eliminated the filibuster for all judicial nominations, clearing the way for Neil Gorsuch to be confirmed with 54 votes (with only three Democrats) and Brett Kavanaugh to be confirmed with 50 (one Democrat).

Partisan Confirmation Votes are Leading to Partisan Supreme Court Decisions

Unsurprisingly, the confirmation of increasingly ideological judges through an increasingly politicized process has affected judicial voting behavior. Until the 1940s, at least 80% of Supreme Court decisions in most years were unanimous, and 5-4 splits rarely crept over five percent. Since 2000, only 36% of decisions were unanimous while 19% were 5-4. While they are on the decline, unanimous decisions are still the most likely Supreme Court results. Some point to this as evidence that the Supreme Court is absent of partisan bias. However, this argument neglects an important nuance. Some Supreme Court cases involve issues that tap into ideological values while many others do not.

A regression analysis of data from the 2018 Supreme Court database shows that cases involving criminal procedure, due process, and the First Amendment—all politically charged issue areas with clearly defined liberal and conservative viewpoints—are significantly more likely than others to produce divided votes. Conversely, cases involving interstate relations, judicial power, or economic activity are significantly more likely than other types of cases to result in unanimous votes. The Supreme Court may value consensus, but increasingly, not when an ideological question is at stake.

Ending the Supreme Court Nomination Lottery

There is no single rule reform or legislation that can depoliticize the Supreme Court. However, two changes could help restore some of the Supreme Court’s legitimacy by lowering the stakes for each nomination and forcing bipartisanship back into the process.

The first involves setting term limits for Supreme Court justices, who can currently serve for life.

This wasn’t a problem in the early years of our Republic, when the average retirement age of the nation’s first ten Supreme Court justices was 60 years old.

But consider the fact that Ruth Bader Ginsburg served 27 years on the Court. Anthony Kennedy served for 30 and Antonin Scalia served for 29. A Supreme Court justice confirmed today could easily be on the court until 2050 or beyond, giving them the power to shape the law for decades and raising the stakes of each nomination. In a recent HarrisX/George Washington University poll, 81% of respondents said they were in favor of some form of term limits for Supreme Court justices. One idea would be to allow each new judge a generous, but not lifelong, tenure of 18 years. This would allow for a predictable appointment schedule: a president would appoint one justice in the first year and one in the third year of a term and judges would not feel pressure to delay retirement until a politically opportune moment arises.

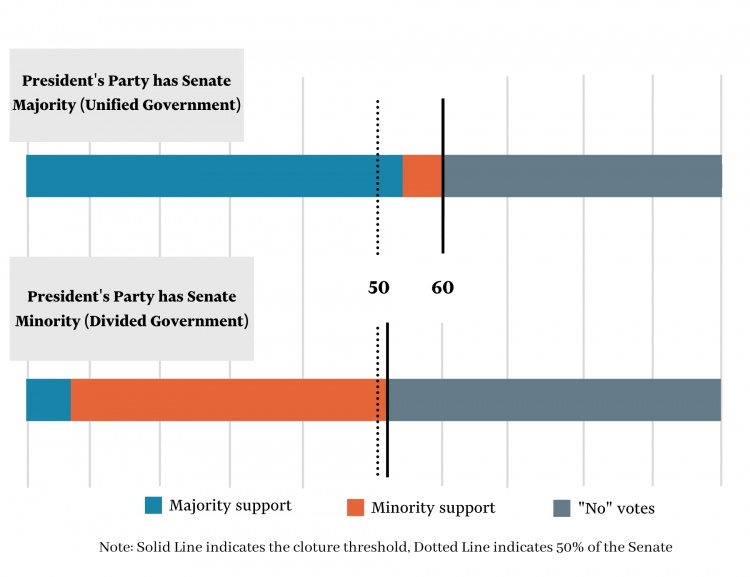

If ending lifetime appointments is too big a lift (it may require a constitutional amendment according to some legal scholars), the Senate at minimum has to restore a semblance of bipartisanship to the process. Between the previous rule for Supreme Court confirmations (60 votes to confirm) and today's rule (51 votes to confirm), there is a middle ground that would require at least some bipartisan support for any confirmation. This is how it would work: If the same party controls the White House and the Senate, 60 votes would be required to invoke cloture and proceed to a vote on a nominee.

During a period of divided government, however, a 60-vote cloture requirement would allow a filibuster to effectively derail any presidential nomination for the Supreme Court, regardless of the quality of the nominee. So, if the Senate is controlled by one party and the president is a member of the other, the cloture threshold should remain 51 votes. This would give the minority party a realistic chance to end debate and move on to a final vote if the nominee appeals to a handful of senators in the opposing party as well.

Recent HarrisX/George Washington University polling also suggests the Supreme Court is one of the last trusted institutions in the United States. When asked about today’s Supreme Court, 65% of respondents said they believe it is working, while only 30% said they believe Congress is working.

But in order to maintain the public’s trust in the Supreme Court, we must combat the dangerous polarization infecting it.

Julia Baumel is a policy analyst with The New Center.