Opportunity Cities and the Mid-Terms

Everyone knows Republicans don’t do well politically in urban areas, but there are lessons from U.S. cities that political conservatives should take away from the GOP’s mid-term performance.

Some races, such as Ron DeSantis’s blowout performance in Miami-Dade County and a few congressional races in the greater New York City metro area, have caught the attention of leaders in both parties. Bread-and-butter issues such as crime and pocketbook issues were key in upending candidates in a Democratic party whose policy objectives were often out of step with the concerns of voters in metropolitan areas.

But another mid-term urban phenomenon deserves attention: the solid performance of Republican gubernatorial candidates in dynamic, Democratically-controlled cities. These cities anchor larger metropolitan areas that we might think of as “opportunity metros” – places that are growing because they offer good jobs and an appealing quality of life.

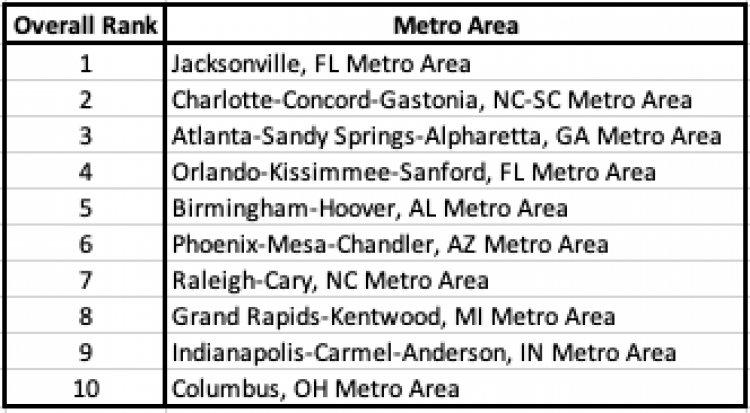

Opportunity metros, as I define them, are major metropolitan areas with a population above 1 million that combine impressive population growth with reasonable housing affordability, strong productivity, a healthy labor market, good wages, and an environment friendly to new businesses. The top ten opportunity metros include familiar high-growth places such as Charlotte, Phoenix, and Atlanta, as well as growing heartland metros such as Indianapolis, Columbus (Ohio), and Grand Rapids (Michigan). A lot of population and economic growth in opportunity metros happens in the suburbs, but the main cities within them always play an essential role.

Rankings are an average of each metro’s rank on 13 economic, labor, and affordability indicators from U.S. Census, BLS, Federal Reserve, and proprietary data sources.

The main cities within these metro areas are predominantly Democratic. Nine of the 10 main cities within these metro areas have Democratic mayors, reflective of their base of voters. For example, Democrats outnumber Republicans by about two to one in Charlotte and Columbus.

And the trends have only improved recently for Democrats in these cities. Joe Biden’s share of the vote in 2020 was larger than Hillary Clinton’s in 2016 in all but one of them. Democratic Senate candidates improved their share of the vote in seven of the ten cities in 2022 compared to 2016. And perhaps unsurprisingly, Democratic House candidates cleaned up in all of them given how their district maps favor them.

Which brings us to the curious case of Republican governors. They grew their share – mostly by double digits – in five of the eight cities in states with a 2022 gubernatorial election compared to 2018. Two of the other three that elected a governor in 2020 also saw impressive GOP gains since 2016. The only city to see double-digit Democratic gains in its share of votes for governor since 2018 was Phoenix, where Trump-backed Kari Lake was solidly outperformed by the gubernatorial winner, Katie Hobbs.

Why are the results among governors so different than the other electoral results?

First, pragmatic governance goes a long way with voters in opportunity-rich places. Among the many reasons people have fled California and New York over the past decade, the overly ideological governance of their political class is an important one. Governors who put household interests – jobs, schools, crime, affordability, reliable and responsive public institutions – before ideological ones do well in opportunity-rich places where people are more interested in building and making a life for themselves than joining this or that cause. Business leaders, workers, and families in dynamic, growing places care more about these issues than climate change, student loan forgiveness, or the massive social spending that national Democrats have hung their reputation on. This helps explain why governors such as Brian Kemp in Georgia, Mike DeWine in Ohio, and Eric Holcomb in Indiana all increased their share of the vote in Atlanta, Columbus, and Indianapolis in the most recent gubernatorial elections. Among Democrats, a pragmatic Democratic governor like Roy Cooper in North Carolina, home to Charlotte and Raleigh, enjoys an impressive approval rating owing to crossover Republicans.

Second, following from the first point, six of the top ten dynamic cities are in states with a Republican governor, and nine of them are in states in which the GOP controls both legislative houses, which creates healthy political competition with predominantly Democratically-run cities. Political competition is often messy, but it is also good for more balanced governance in general and typically tends to lead to more pragmatic policy solutions than we see at the federal level or states with an overly dominant party

Third, opportunity metros are places where people believe in the merits of hard work and the possibility of upward mobility, and Republican candidates simply talk about this more. The common-sense belief that effort and hard work lead to personal success is widely shared by the working class, middle class, and just about every demographic group – except the most committed progressives. When common-sense Republican governors talk about why we need good schools, why easing regulatory burdens help small business owners, and so on, their words resonate with a lot of common-sense Democrats in urban areas whose political overclass arguably stopped thinking about them a while ago.

The lesson is clear: residents of dynamic, growing cities increasingly want pragmatic solutions more than ideological fixes. Political conservatives should give this some thought.

Ryan Streeter is the director of domestic policy studies and the State Farm James Q. Wilson Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.