Why Bhutan Is the Happiest Developing Nation on Earth

What can a tiny Himalayan country nestled between India and Tibet teach the world? More than you might think.

A growing number of Western industrial democracies are embroiled in turmoil. A former U.S. president promises “death and destruction” if multiple legal proceedings don’t go his way. Dozens of French cities are smoldering after weeks of violent protests over unavoidable pension reforms. Meanwhile, Bhutan peacefully and consistently fulfills its citizens’ aspirations. This success isn’t accidental. Bhutan’s legal edict of 1629 states that “if the government cannot create happiness for its people, there is no purpose for the government to exist.” National happiness has since become Bhutan’s governing hallmark.

This is the first of a two-part essay exploring how Bhutan became the world’s happiest developing country, and what its experience can teach us. Bhutan is not perfect, and its achievements have not been trouble-free. As rising wealth fails to make many societies happier, however, Bhutan reminds us that communities and nations need more than money to thrive.

+++++++

I will protect you as a parent, care for you as a brother and serve you as a son. I shall give you everything and keep nothing. I shall live such a life as a good human being that you may find it worthy to serve as an example for your own children. I have no personal goals other than to fulfill your hopes and aspirations.

King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck

Bhutan’s fifth (and current) king

Bhutan’s modern journey toward happiness began in 1972, when King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the fourth in the Wangchuck line, became the world’s youngest monarch at the age of 17. The Dharma King, as he became known, immediately displayed wisdom beyond his years. “Gross national happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product,” he proclaimed. The idea of Gross National Happiness (GNH) has since become the guiding principle of Bhutan’s government, enshrined in Article 9 of its constitution. Transforming GNH from theory to practice has involved decades of deliberate effort, meticulous planning, and mindful execution.

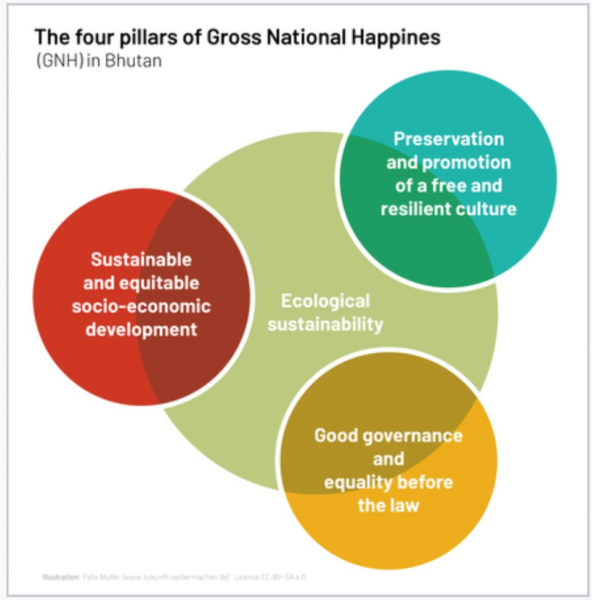

GNH in Bhutan is based on four fundamental pillars and nine accompanying objectives, each mindfully optimized in an evolving, multi-variable dialectic. Bhutan’s current prime minister, Dr. Lotay Tshering, explains: “If a policy does not promote our happiness objectives, if it is not environment-friendly, or if it isn’t certain to result in greater well-being for the Bhutanese people, then that policy will never be approved in our country.” Bhutan’s success in implementing GNH has consistently generated high levels of recorded personal satisfaction and public trust in the government.

The first pillar of Bhutan’s commitment to happiness is equitable and sustainable socioeconomic development. Bhutan considers the material well-being of every citizen as a fundamental right. Every citizen has access to clothing, housing, education, and healthcare, as well as legal protections for speech, private property, voting rights, and equal justice under law. No one is left behind. In return, Bhutanese citizens are expected to work, protect their country’s sovereignty and culture, pay taxes, and actively participate in community functions. The Dharma King summarized this social contract succinctly: “A little effort on your part will be much more effective than a great deal of effort on the part of the government.”

GNH’s second pillar is cultural preservation. Bhutan is a deeply Buddhist country that prizes peace, nonviolence, compassion, and tolerance. Preserving the nation’s distinct Mahayanist cultural heritage, including support for its monarchy, is fundamental to the identity of every Bhutanese citizen. Public virtues matter. Multiple social guidelines are followed, including some that seem restrictive by Western standards. For example, smoking is prohibited in most indoor and outdoor locations, traditional dress is encouraged, and social media is monitored in relation to GNH goals. Volunteerism is widespread.

Maintaining cultural cohesion hasn’t always been easy. During the 1990s, Bhutan fought an internal war, deporting more than 100,000 mostly Nepalese residents who espoused anti-monarchical, socialist ideals. Their demands represented a clear threat to Bhutan’s ancient and most respected traditions. Some refer to these years as Bhutan’s darkest; others see them as Bhutan’s most important. During these years of conflict, it is estimated that 20%–30% of Bhutan’s population was deported or voluntarily fled. The king himself engaged directly in several pitched battles, further securing the devotion of his people.

The third pillar of Bhutan’s commitment to GNH is ecological sustainability. Bhutan values economic growth, but it places equal emphasis on ensuring that growth is sustainable, equitable, and inclusive. As Prime Minister Tshering explained, if growth initiatives do not benefit all in an environmentally responsible manner, they do not receive government support.

Bhutan’s fourth pillar is good governance. The nation’s democratic traditions have deepened over the past seven decades. The groundwork for democratization was laid under King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck in 1952, with the establishment of a ruling National Assembly. Parliamentary elections were further formalized by Bhutan’s fifth and current monarch and enshrined in the 2008 constitution. The country boasts a well-functioning legal system, a robust anti-corruption commission, and an effective, two-party parliament. Bhutan’s leaders are held accountable for their actions through a culture of transparency.

While Bhutan’s GNH philosophy is rooted in these four pillars, progress is meticulously assessed through nine additional domains: psychological well-being, physical health, education, time use, cultural diversity, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity, and living standards. Bhutan has developed sophisticated metrics and polling methodologies to measure and monitor progress across each of these domains in collaboration with Oxford University researchers and the Center for Bhutan Studies. These methodologies and domains align with the country’s adherence to Buddhism’s “middle path,” which emphasizes balanced actions instead of extreme, stop-start approaches.

Prime Minister Tshering emulates the modest lifestyle of the king. He refused a salary increase above $28,000, donating the additional amount to charity. His remuneration is one of the lowest among senior elected officials worldwide, amounting to less than 2% of that of his counterpart in Singapore. In addition to his role as the country’s leading elected official, Tshering is also a practicing medical doctor. He volunteers his time and professional services to treat patients on weekends. Bhutan’s monarchical and ruling elites are recognized for their exemplary public service. No one doubts their desire to fulfill the hopes and aspirations of their fellow citizens.

Bhutan’s economic performance is equally commendable, with an annualized GDP growth rate of 7.5% from 2000 to 2019. Over the first two decades of the 21st century, Bhutan’s GDP quintupled, and per capita income multiplied over 4.5 times, making it one of the fastest-growing developing countries. Like every other country, Bhutan had to navigate the challenges of the COVID pandemic. This has meant making difficult choices, like closing the border to visiting foreigners and promoting a national vaccination plan. The king himself trekked by car, horse, and foot to remote hamlets to assure his subjects that government plans would protect them. As revenues in the tourist sector fell to zero, the king also supplemented the incomes of those who suffered most, and granted a Kidu, or loan-interest waiver, to those who found themselves unable to pay their debts. Today, Bhutan charges the highest tourist tax in the world – $200 per day for most visitors – to supplement the incomes of those who are still recovering.

Bhutan’s journey toward becoming the world’s happiest developing country has been led by an enlightened monarch and rooted in the principles of Gross National Happiness. The nation’s holistic approach to development goes beyond economic indicators. It has resulted in a society that values inclusivity, sustainability, and universal well-being.

Terrence Keeley is the author of Sustainable: Moving Beyond ESG to Impact Investing, and the CEO of 1Point Six LLC.

Editor’s Note: What lessons Bhutan offers the rest of the world will be explored by the author in more detail in the second essay of this series, to be released tomorrow.