Beyond the 'Private Option' for Medicaid Expansion

Less than a year after low-income Arkansans started receiving health coverage under the Affordable Care Act's controversial Medicaid expansion, the state is declaring its so-called "private option" experiment a success.

Hospitals saw fewer uninsured patients, state coffers were spared millions in health care costs and private insurers reported record-low premium hikes. Most important, Arkansas' uninsured rate fell from 23 percent to 12 percent, the sharpest drop in the country.

But lawmakers in Arkansas, where Gov. Mike Beebe is a Democrat and the legislature is controlled by Republicans, have already asked the federal government for adjustments to their groundbreaking plan, under which Arkansans used Medicaid dollars to purchase private health insurance on the insurance exchange created under the ACA. Meanwhile, other states are customizing their own alternative approaches to expanding Medicaid to cover adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,105 for an individual).

"It's an iterative process," said Matt Salo, director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. "States are probing the defenses of the HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) fortress to see what they can get approved," he said.

Ever since the U.S. Supreme Court made the federal health law's Medicaid expansion optional for states, the debate over expansion has become a proxy for supporting or opposing Obamacare.

After the November elections, more states are expected to reconsider their largely political decisions to pass up millions in federal dollars that can be used to improve the health of their residents.

"This is a fight within the Republican party," said Joan Alker, director of Georgetown University's Center for Children and Families. "After the election, when governors and lawmakers feel less threatened, we should see more movement," she said. Alker and others cite Idaho, Montana, Nebraska and Florida as possible converts.

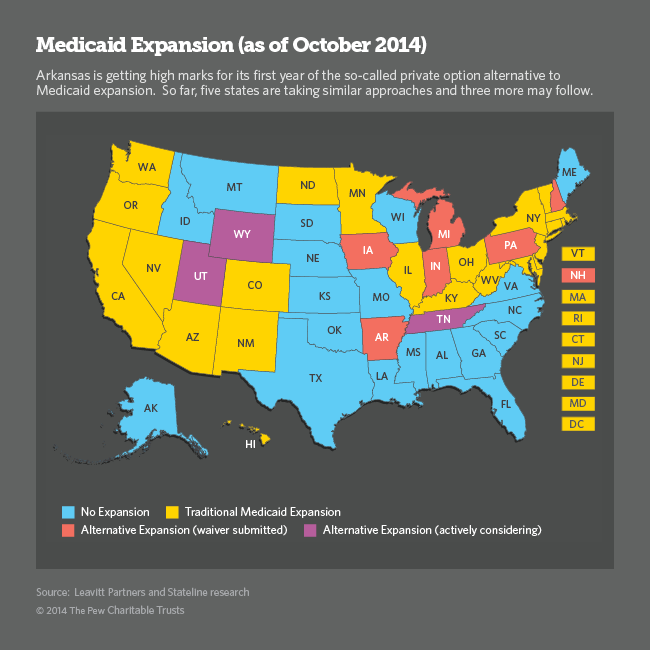

So far, 28 states and the District of Columbia have decided to expand Medicaid and 22 have not. Of the 28 states that have expanded the federal-state program, 19 have Democratic governors and nine -- Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio and Pennsylvania -- are led by Republicans.

Six states have asked HHS for special permission to put their own stamp on the way beneficiaries receive and pay for care, instead of simply adding them to the rolls of traditional Medicaid. Arkansas was first to get approval in 2013 for its private option, which this year allowed 210,000 Arkansans to use Medicaid dollars to purchase private health insurance on the state's insurance exchange.

Iowa was next, receiving permission to substitute private insurance for Medicaid for a portion of its newly eligible adults, charge copays and eliminate nonemergency transportation; Pennsylvania got approval in July to take a similar approach with enrollment starting next month. Michigan chose not to switch to private insurance, but got federal approval to charge newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries copays that can be reduced as a reward for engaging in healthy behaviors. New Hampshire and Indiana are next in the queue.

Utah is among a handful of states actively considering an alternative Medicaid expansion, and Republican Gov. Gary Herbert is expected to be the next to announce a plan. He will then have to ask approval from state lawmakers and the federal government. Tennessee and Wyoming, both led by Republican governors, are also considering alternatives to traditional Medicaid expansion.

A GOP Debate

The debate within the remaining nonexpansion states is largely between conservative Republicans, who oppose Medicaid expansion in any form, and moderate Republicans, who are open to alternative ways to use federal money to cover more people. The Obama administration is so eager for more states to expand Medicaid that it is offering significant flexibility in the way states implement the health law's historic expansion of the nearly 50-year-old Medicaid program.

At stake is $424 billion in federal money through 2022 to cover 6.7 million uninsured adults, according to a new study by the Urban Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that nearly 5 million of them are ineligible to receive federal tax credits on the insurance exchanges because their incomes are below the federal poverty level ($11,670 for an individual).

For states that choose to expand Medicaid -- no matter what approach they take -- the federal government will cover the entire cost of coverage in 2014, 2015 and 2016. After that, full federal coverage declines each year, tapering to 90 percent in 2020 and beyond.

Given the administration's flexibility, all new expansions are expected to include some type of customization. So far, states are seeking permission to charge copayments to cover part of the cost of visiting a doctor's office or hospital emergency department. Other common requests include policies that reward consumers for adopting healthy lifestyles and "health savings accounts" designed to encourage consumers to sock away money for future health expenditures.

Most of the requests reflect decades-old Republican principles that low-income Medicaid beneficiaries should take personal responsibility for their health by making healthy lifestyle choices and more economical decisions about their care.

In addition, most states are seeking to bring Medicaid benefits in line with the benefits received by middle-class people who pay for private insurance. For example, most states are asking to eliminate special services such as nonemergency transportation and regular diagnostic screenings for 19- and 20-year-olds, which are covered under traditional Medicaid.

Alker and other consumer advocates are hopeful that more states will choose expansion, but they are closely watching states' negotiations with the federal government. The worry is that too much administrative complexity combined with even minimal copays could result in lower sign-ups and less use of the health care system.

For example, copays may make sense in the private insurance market, Alker said, but research shows the introduction of even nominal fees in the Medicaid program in the past has resulted in some low-income consumers missing needed care.

As for nonemergency transportation, studies show that their most common use is for kidney dialysis and behavioral health therapy, both of which are considered essential services. Consumer advocates argue that eliminating rides to important medical appointments could increase overall costs in the long run.

Good for the Market

One of the biggest benefits of Arkansas' private option has been its effect on the commercial health insurance market, said Robin Arnold-Williams, senior health care adviser with health care consultants Leavitt Partners. Early estimates indicate next year's insurance rates in the state will be an average of 2 percent lower than this year, and the statewide insurance market now includes five carriers, compared to just one statewide carrier in the past.

Under the Arkansas plan, residents with incomes up to 138 percent of poverty were allowed to sign up for private health insurance on the exchange starting in October 2013. But in approving its proposal, the federal government required the state to exclude anyone who self-attested to being in poor health or "medically frail." About 10 percent did so. As a result, the sickest and costliest patients were served under traditional Medicaid.

Furthermore, as a group, the people using Medicaid dollars to purchase insurance on the exchange were younger and healthier than other exchange customers, and they made up 75 percent of the total. In a small state with scant insurance competition, adding that low-cost population to the exchange pool might have rescued the state's fledgling exchange from a "death spiral," Williams said.

The private option also was expected to improve patients' access to health care providers, because doctors in private networks are paid higher fees than those who bill Medicaid, and to reduce administrative difficulties for consumers whose rising incomes force them to switch from Medicaid to private insurance, by allowing them to maintain their health cards and doctors. In the coming months, Arkansas Medicaid officials will report on whether those hopes came to fruition.

Christine Vestal is a senior writer at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, where this piece originally appeared.