Time to Worry About Long-Term Unemployment

Vacations are different from weekends.

Two days off at the end of the week is nice, but anyone who's ever felt Sunday-afternoon angst knows you need a lot more than that to get a true respite from the working world. Three or four days in, you finally start relaxing. After a week, you stop compulsively checking your e-mail. Another week and PowerPoints and conference calls begin to seem a fanciful memory, not unlike payphones and smoking in restaurants.

Unfortunately, the deepness of the relaxation is matched only by the harshness of the wake-up call. Upon returning to the office, you are at once inundated and overwhelmed, unable to remember what you were working on or, worse still, why it was important.

For most Americans, a really long vacation might last for a couple of weeks. Now imagine how you'd feel if you were out of work for a year. You'd notice your skills depreciating. Your self-esteem might take a hit. And if you didn't have a set job to return to, you might start to doubt if you'd be able to find a job at all.

If you can appreciate these feelings, you can begin to get a sense of why long-term unemployment is important.

Long-Term Unemployment at Historic Highs

You may have heard that unemployment has been dropping recently. It's true. At 5.8 percent, it's only a quarter above its 2007 average.

But seven years after the onset of the Great Recession, long-term unemployment remains at 1.9 percent. Although it has steadily fallen from its record of 4.5 percent in 2010, it's still higher than it was at any time between 1983 and the Great Recession.

In normal times, most unemployment is of the short-term variety, which is defined as spells lasting 26 weeks or less. Take a look at the figure below, which comes from my new report, "Uncovering the Labor Market Recovery," published last week by the Century Foundation. From 2000 to 2007, long-term unemployment constituted less than a fifth of total unemployment, on average.

But in the aftermath of the recession it spiked, grabbing a 45 percent share in 2010. Four years later, the long-term unemployed are still a third of all unemployed. What that means is one in every three unemployed workers have been without jobs for more than 27 weeks. That's 2.9 million people.

So while the short-term unemployment rate is just 4.1 percent above its pre-recession average, the long-term unemployment rate is still elevated by a staggering 130 percent. As of October, the average unemployed worker had been out of work for 32.7 weeks -- nearly a doubling of the average duration of unemployment in 2007.

Duration matters. Like a summer vacation on steroids, time spent out of work causes productive potential to erode. What's more, the long-term unemployed often must switch industries or change occupations, which requires not only not losing old skills, but acquiring new ones.

Employers know this. So the longer someone sits on the sidelines, the larger the stigma they must overcome in making their case to recruiters. And the longer the drought, the more skills dry up, which makes finding a job harder still -- a vicious cycle.

Effects of Long-Term Unemployment Can Be Permanent

The unemployed themselves aren't the only ones hurt by this unforgiving pattern. At the macro level, sustained labor underutilization can permanently harm an economy's productive capacity. Economists refer to this as hysteresis, a term borrowed from physics that describes situations in which temporary perturbations have permanent consequences. In our case, persistence in long-term unemployment may mean strained safety nets and diminished living standards for years to come.

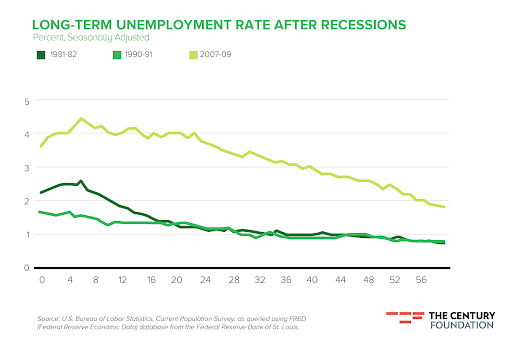

It's too early to tell whether the Great Recession's long-term unemployment legacy will linger. But the next figure suggests just how unusual our present situation is. It shows the evolution of the long-term unemployment rate in the five years following the month in which the overall unemployment rate peaked during the three most recent recessions (excluding the minor recession of 2001).

In each case, long-term unemployment considerably exceeded pre-recession levels. But in the 1981-82 and 1990-91 recessions, it declined to normal levels within about two and a half years. (From 1980 to 2007, the long-term unemployment rate averaged 1.0 percent.)

But the Great Recession was different. Not only did the long-term unemployment rate reach nearly twice the level it did during the two previous recessions, but now, five years out, it's still double its pre-recession norm. That's not a good sign.

What Makes the Great Recession Different?

So why has the Great Recession been different for long-term unemployment -- and what does this imply for policy? These questions are not easy, and remain fairly unresolved. However, a recent Brookings paper by Princeton economists Alan Krueger, Judd Cramer, and David Cho offers a few important insights.

In one sense, the long-term unemployed are a different species from those unemployed only for short periods. They have much greater difficulty finding jobs; indeed, the authors find that, from 2008 to 2012, only about one in ten long-term unemployed returned to full-time work within a year. Not surprisingly, the long-term unemployed are also more prone to stop looking for work -- that is, to withdraw from the labor market.

Consequently, the long-term unemployed exert little pressure on hiring or wages, which may help explain why we have not experienced deflation even as the unemployment rate remained high. For purposes of prices and wages, the long-term unemployed have seemingly had the effect of artificially inflating the unemployment rate.

But in another important sense, the long-term unemployed are just like the rest of us. The study finds that, contrary to popular conception, the long-term unemployed are spread widely across demographic and occupational groups. In other words, the long-term unemployed are unlucky.

When consumer demand collapsed during the Great Recession, unemployment spiked. When it did, some laid-off workers got trapped in the long-term unemployment vortex, often through no fault of their own. Many remain mired there today.

Employment policies should serve the needs of these hard-luck workers. Education and training programs that equip displaced workers with new skills are a good place to start, as are incentives that militate against employer biases. But as the Brookings study suggests, the diversity of the long-term unemployed necessitates a potluck of solutions, carefully calibrated to individual circumstances.

Most importantly, we must act now: Getting the involuntarily idle back to work is not just for their sake; it's for ours too. Let's hope it doesn't take much longer.

Mike Cassidy is a policy associate at the Century Foundation.