SNAP's Fading Work Requirements

Americans want to provide assistance to poor families going through tough times. For most of its history, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, has fulfilled that goal by ensuring that poor Americans could put food on the table. But when economic factors improve and jobs are available, the need for SNAP should decline. Unfortunately, policy choices since 2000 have weakened SNAP so that it is not responding properly to improving economic conditions, promoting work successfully, or maintaining its focus on the poor.

After the recession ended in 2009, average monthly SNAP participation continued increasing, climbing from 33.5 million to 46.5 million in 2014. It remained over 45 million as recently as May 2015. This was unexpected. In 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had predicted that participation would be down to 39.6 million by 2015.

Before the year 2000, SNAP caseloads and the unemployment rate moved in tandem. When the economy hit a rough patch, food stamps provided help, and when things improved, the number of recipients, after a short delay, dropped. After 2000, the pattern changed: Enrollment increased even with improvements in the economy. As one USDA official explained, SNAP caseload changes have slightly lagged behind economic conditions in the past, but "the current lag is longer than ever before."

This new trend is troubling, and since the CBO underestimated SNAP's growth before, the agency's current prediction that participation will drop to 37.5 million by 2020 seems overly optimistic. It now appears that caseloads are staying high because the program has substantially changed.

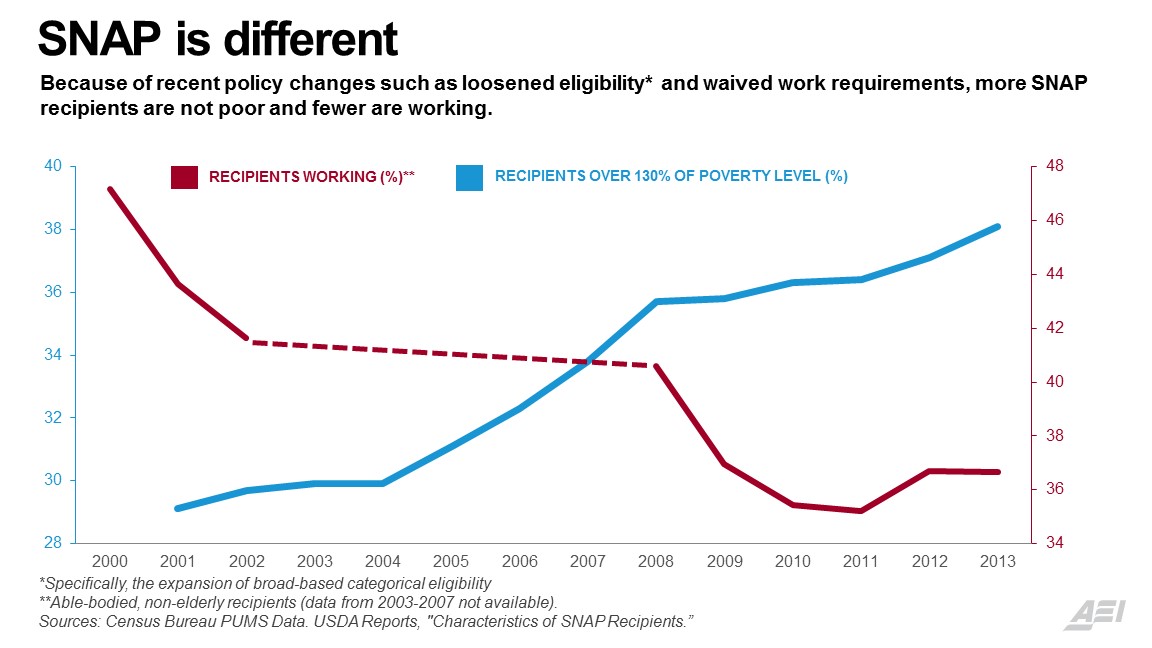

In the years after welfare reform in 1996, SNAP became a work-support program for individuals who were able to work but earned little. And that is a good thing — American social policy should help low income working families. But increasingly, recipients who could be working are not. Since the year 2000, the share of able-bodied, non-elderly recipients who work has dropped from nearly half to only 37 percent.

A third concerning trend is that SNAP benefits are more often going to individuals who are not poor. Today, almost four in ten SNAP recipients make more than 130 percent of the poverty level in a year ($31,518 for a family of four) — a 30 percent increase since 2001.

These trends are largely caused by policy choices. First, in 2000, the Clinton administration issued a regulation allowing "broad-based categorical eligibility." This may sound like technical language, but it fundamentally changed the program by allowing states to enroll anyone who gets any aid or service from the federal welfare program. As a result, 42 jurisdictions make households categorically eligible for food stamps by passing out brochures or 1-800 numbers and counting that as a "service." Recipients who become eligible this way do not have to pass SNAP's long-standing income and asset tests, and merely need to show that they have income less than double the poverty line (which is $48,500 annually for a family of four). Likewise, changes in reporting requirements in the 2002 Farm Bill made it easier for recipients in many states to continue to receive SNAP even after their income rises. These changes have increased the total number of recipients and the share with higher incomes.

We can see the impact of these policies by looking at state-level data. Consider the state of Utah, which does not utilize broad-based categorical eligibility: SNAP participation responded to need during the recession and has already seen significant declines in the recovery. After peaking in 2012, Utah SNAP caseloads dropped by 20.1 percent through 2014, compared with a 2.3 percent decline nationally since the 2013 peak. Despite some people's fears that a stingier program would increase hunger, Utah has seen a slight decrease in reports of what USDA calls "very low food security." Meanwhile, Colorado, which has broad-based categorical eligibility and simplified reporting, saw its unemployment rate go down to 4.9 percent, but it still has a SNAP caseload more than double its 2007 level.

Another significant change was a weakening of work requirements. After welfare reform, able-bodied adults without dependents were required to work to receive SNAP or lose benefits after three months. In recent years, though, many states have chosen to waive this requirement, and in 2015, even as unemployment has dropped, 41 states are still using waivers to exempt residents from the work requirement — likely leading to lower work rates.

Economist James Ziliak's research finds that the economic downturn can explain only about half of the recent increase in SNAP participation. It seems likely that these policy changes are behind much of the rise in enrollment, the increase in recipients with higher incomes, and the declining work rates.

To reverse these trends, states should re-extend work expectations to the non-elderly, able-bodied population without dependents, and end broad-based categorical eligibility. The most effective way to ensure that recipients of all public-assistance programs gain employment is by having a clear requirement and expectation of work. Ending broad-based categorical eligibility would also ensure that governmental resources are dedicated to the truly needy.

Providing for the needs of the poor and ensuring no one goes hungry are obligations we have as Americans. To be most effective, SNAP needs to respond to economic conditions, focus on the poor, and help those who are struggling to find paid employment.

Robert Doar is the Morgridge Fellow in Poverty Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. From 2007 to 2013, he was the commissioner of the New York City Human Resources Administration.