Our Safety Net Misses the Poorest

Safety-net programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit and SNAP (formerly food stamps) lifted millions of Americans out of poverty last year, new Census data show, and the nation made historic gains in health coverage. However, severe poverty has worsened in the last couple of decades, reflecting the weakening of the safety net for individuals who can't work, are unable to find work, or can find only part-time, sporadic work.

An important new book by Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer — $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America — offers a sobering account of parents and children living in desperate poverty and shows how the welfare reform of the mid-1990s has left millions behind. The authors intimately portray families from places as diverse as Chicago and the Mississippi Delta, finding that the number of households with monthly cash incomes equivalent to less than $2 per person per day — a standard of poverty usually associated with poor countries — has more than doubled since 1996, to 1.5 million.

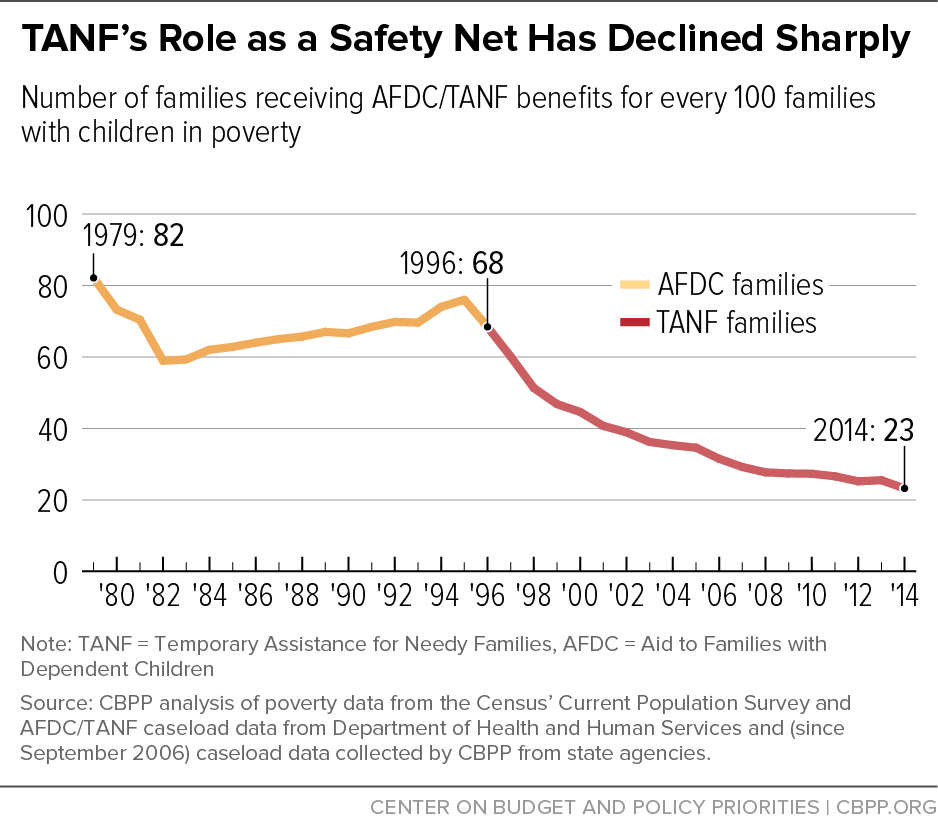

Part of the problem, Edin and Schaefer explain, is Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the cornerstone of 1996's welfare-reform law. Created as part of a dramatic shift in income-assistance policies for low-income families with children, TANF replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which had chiefly served families with little or no earnings. TANF offers cash assistance to far fewer families than AFDC did and includes time limits and stricter work requirements.

At the same time, policymakers expanded assistance for moderate-income working families. Most notably, they strengthened the Earned Income Tax Credit and medical and child-care programs and created (and later expanded) the Child Tax Credit.

The evidence suggests that while many parents moved from welfare to work in the strong economy of the late 1990s and child poverty declined, the percentage of children in deep poverty — defined as cash income below half of the poverty line, or less than $12,115 a year for a family of four — rose by more than one-third between 1995 and 2005. And TANF has weakened significantly as a safety net for the nation's neediest families. In 1995, AFDC lifted out of deep poverty some 62 percent of the children who would otherwise have been below half of the poverty line. By 2010, this figure for TANF was only 24 percent.

By 2014, TANF provided a temporary safety net in the form of cash benefits to only 23 families with children for every 100 families in poverty, down substantially from 68 assisted families in 1996.

In some states, TANF barely exists as a safety net for poor families. In twelve states, fewer than ten out of every 100 families living in poverty receive TANF cash assistance.

Even as families struggled financially during and after the Great Recession, many states made policy and administrative changes that significantly cut their TANF caseloads. And even though the goal of welfare reform was to move families from welfare to work, states spent only 8 percent of their state and federal TANF funds on work activities in 2013, with 14 states spending less than 5 percent.

Policymakers should strengthen existing programs — or create new ones — to help the $2-a-day poor and other families with extremely low incomes. They can start by reforming TANF. Specifically, they should 1) create a new accountability measure that encourages states to serve more families in need; 2) reward states that place more TANF recipients in jobs, not those that simply reduce their caseloads; and 3) require states to spend a specified share of federal and state TANF resources on TANF's core purposes — cash assistance, employment assistance, and work supports.

Ife Floyd is a policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.