Against Regulatory Complexity

With the July 21 anniversary of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act now upon us, it’s a good time to reflect on how this type of Byzantine legislation spawns a convoluted network of tangled regulations.

When recently unveiling his Financial CHOICE Act, House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling highlighted a key principle behind his efforts to combat this overgrowth: “Simplicity must replace complexity.” The chairman’s focus on regulatory complexity is appropriate.

In many ways, regulations are like a computer’s operating system, establishing processes and parameters within which programs must operate. But anyone who has undergone the experience of “upgrading” an operating system only to find her computer sluggish and unresponsive knows that complexity is not always a desirable feature. Steven Teles, a political scientist with Johns Hopkins, made a similar comparison when he famously referred to American policy as a “kludgeocracy,” an ever-expanding series of “inelegant patch(es)” meant to solve short-term problems, but which ultimately hinder system performance.

A recent analysis showed that Dodd-Frank accounted for nearly 30,000 new regulatory restrictions — more than all other laws passed during the Obama administration combined. These new regulations, authorized by a Congress in crisis mode, were piled on top of more than one million existing regulatory restrictions. Even former Senator Chris Dodd, one of the bill’s namesakes, admitted just after the bill’s passage that “no one will know until this is actually in place how it works.” Scholars subsequently argued that the regulatory uncertainty exacerbated by Dodd-Frank could explain the slow recovery. At the time, however, some facts were clear: Dodd-Frank would increase regulatory complexity, induce uncertainty, and line the pockets of regulatory compliance experts.

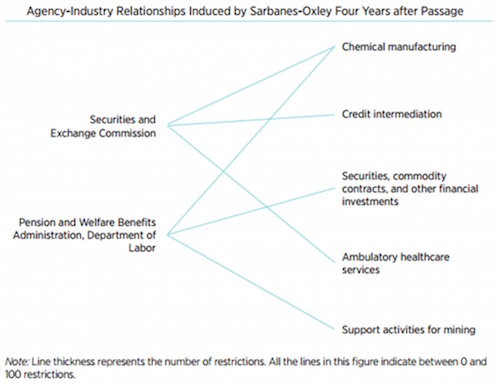

To an unprecedented degree, simply ascertaining the relevance of regulations stemming from an act of Congress now requires regulatory compliance expertise. To illustrate, consider a simple visualization of regulatory restrictions originating from another major financial regulatory law, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Sarbanes-Oxley, which dealt with audits and financial reporting, affected public companies in all sectors of the economy and induced some regulations that specifically targeted a handful of industries. Textual analysis of those regulations shows that five industries were directly targeted by regulations from two federal agencies:

Sarbanes-Oxley was, of course, a significant regulatory overhaul in its own right. In 2012, the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board went so far as to call it one of the reasons for slow economic growth. Furthermore, much of the effect of Sarbanes-Oxley stems from the creation of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, a regulatory entity that awkwardly straddles the public-private divide with considerable control over auditing firms and — indirectly — the public companies they audit.

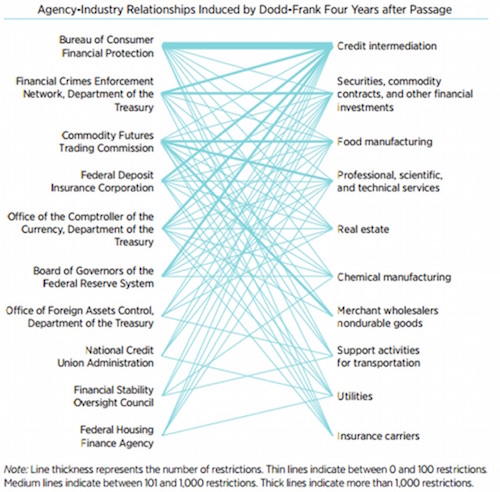

Nonetheless, even allowing for the additional complexity of referencing accounting standards that are not formally published as regulations, Sarbanes-Oxley is a model of simplicity compared to Dodd-Frank. Consider a similar visualization of the agency-industry relationships emerging from Dodd-Frank — which, for the sake of visualization, is limited to only 10 agencies and 10 industries. In fact, at least 32 different agencies have promulgated rules under the statutory authority of Dodd-Frank:

In the post-Dodd-Frank world, understanding which regulations are relevant to a business’s activities has become immensely more difficult. Many sectors of the economy were newly exposed to regulations from a multitude of unfamiliar agencies. Duplicative and contradictory rules became a fact of life.

In 1788, James Madison worried that laws may become “so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood.” He was right to worry: current regulatory code is so complex and voluminous that, rather than spend three years reading it, I helped create text analysis software that uses machine learning to assess the probability that a given regulatory restriction targets a specific industry. But even with the insights of machine learning and text analysis software — or regulatory compliance experts who bill by the hour — considerable uncertainty remains. Regulatory agencies, themselves, are, increasingly, unfamiliar with their own regulations.

When there are more rules in place than anyone can read, and interpretation of those rules and their scope is determined by the regulators themselves, businesses must pay for experts to filter the rules that are truly relevant from the rest. Meanwhile, businesses must also keep an eye on new rules coming down the pipeline and the possibility of reinterpretation of old rules. For both federal regulations and statutes, an irrelevant requirement only remains irrelevant until a bureaucrat, or a federal prosecutor, decides otherwise.

Regulatory complexity engenders uncertainty. That may not be a problem for some politicians; but for anyone who must comply with regulations, complexity and uncertainty can be paralyzing. Simplifying the complex regulatory regime imposed by Dodd-Frank is an application of another lesson from the world of computer programming: iterative design can correct serious errors and reduce unnecessary complexity.

Patrick A. McLaughlin is a senior research fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Chad Reese is the assistant director of outreach for financial policy at the Mercatus Center.